Education is a vital sector of national development, particularly in a populous country like Nigeria where youths below 24 years of age constitute majority of the population. The challenge of education in Nigeria is both quantitative and qualitative. The educational policies and priorities of the Federal government have evolved in response to changing political and economic circumstances. As far back as the early sixties, free education was in place in the then Western Region. The priority after independence was to give access to education to the masses, while producing high level and medium level manpower, much needed for the country’s development. Priority was also given to the training of technical manpower. This translated into the creation of universities and polytechnics, as well as technical colleges across the country. However, glaring disparities emerged between northern and southern Nigeria in the development of education. The advent of oil boom in the early seventies brought about significant changes in the educational focus, with the Federal Government enforcing more uniform educational policies, such as the Universal (Free) Primary Education (UPE) scheme in 1975. A comprehensive National Policy on Education was launched in 1977. Besides, in response to the dearth of skilled medium level technical manpower, a “Crash Programme” for the training overseas of thousands of young Nigerians (at post-secondary level) in engineering and technical courses was put in place in the mid-seventies, under cooperation agreements with several countries in Western and Eastern Europe, the United States and Canada, etc.

FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION (FME)

Mandate and Mission

National Minimum standard Act Number 16 of 1999 and the Constitution (chapter 2, Section 18) mandated the Federal Ministry of Education (FME) to oversee policy development, data collection and management for educational and financial planning, and quality control in the educational sector. The Ministry also ensures cooperation, collaboration and coordination on educational matters at national and international levels. It has the additional responsibility of ensuring that Nigeria effectively participates in and benefits from the vast knowledge available globally and the ongoing revolution in New Information and Communication Technologies (NITC).

Structure

The Federal Ministry of Education is structured into five departments:

• Basic and Secondary Education, Higher Education.

• Technology and Science Education.

• Educational Support Services.

• Federal Inspectorate Service.

• Service departments (Planning, Re-search and Statistics, Administration and Supply, and Finance and Accounts).

There are also three statutory units: Press, Legal and Internal Audit.

Role of the Three Tiers of Government

The Federal Ministry of Education is relayed at the state level by the state ministries of education in the implementation of national education policies and programmes. The state ministries in turn work with the local education authorities to develop education at the local level. The bulk of secondary schools in the country are under the purview of state governments, which are also directly responsible for a considerable proportion of the nation’s tertiary institutions. Local governments have statutory managerial responsibility for primary education, with the federal and state governments exercising appropriate oversight functions.

NATIONAL EDUCATION POLICY (NEP 2004)

Structure and Hierarchy

The National Policy on Education (2004) stipulates a 6-3-3-4 structure offering six years of primary, three years of junior secondary, three years of senior secondary and four years of higher education.

This brought the country in line with the standard and format applied in most countries. However, the two-tier, 3/3 structure consisting 3 years of junior and senior secondary schooling respectively, became operational in 1982. Prior to this, secondary education was for a duration of 5 years sanctioned by the West African School Certificate (WASC) or General Certificate of Education (GCE – Ordinary Level) followed in most cases by a 2 year programme leading to the Higher School Certificate (H.S.C.) or GCE – Advanced Level, which gave direct access to degree programme in the university.

Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) – Universal Basic Education (UBE)

Primary and Junior Secondary Education

Early childhood education constitutes the foundation of the Nigerian educational system. This comes in the framework of Universal Basic Education (UBE) scheme, which covers the first nine years of education comprising 6 years of primary and 3 years of junior secondary education. During these first nine years, promotion from one class to the next is based on continuous assessment but is automatic. At this stage, the government’s role is essentially to set standards, define curriculum guidelines, train teachers and ensure supervision and quality control for the educational service provided by both public and private sector establishments. The scheme is monitored by the Universal Basic Education Commission, UBEC, based on the UBE law which makes basic education a right for all children. The law also stipulates adult literacy, non-formal education, vocational training and skill acquisition programmes, as well as the education for special groups, including as nomads and migrants, street children, disabled people and “Al-majiri” (Quranic school children). The curriculum for junior secondary education is both prevocational and academic, consisting of basic subjects that are expected to prepare students for senior secondary education and empower them with some prevocational skill. Secondary education, also referred to as post-primary education is offered by institutions such as secondary schools, colleges, grammar schools and high schools. Students who have completed junior secondary school immediately proceed to senior secondary school for post-basic education.

Senior Secondary

The senior secondary level is broad-based and includes not only academic curriculum designed for general secondary schools but also curricula provided in different technical colleges and vocational centres. It also encompasses adult and non-formal education for a good number of young people who do not reach the senior secondary level, as well as Islamic education, which forms an important traditional part of the formal and informal delivery of education in some states. Under the current 6-3-3-4 educational framework, senior secondary education concludes with the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE), administered by the West African Examinations Council (WAEC). Students may also take National Examination Council (NECO) examinations. Individuals desiring to further their education in universities and polytechnics have to take the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) examination, a competitive harmonised entrance examination in which candidates must score above a cut-off mark to qualify.

Teacher Education

There are currently over 67 Colleges of Education for the training of primary and secondary school teachers across the country. Two or more colleges were established in some states either by the federal and state governments or by private organizations. In addition to colleges of education, university faculties of education and the schools of education of some polytechnics have the mandate and facilities to train teachers particularly for secondary schools. Nigeria has a long history of teachers training. It should be recalled that the first teachers training institution in Nigeria is acknowledged to be that set up by the church Missionary Society in Abeokuta in 1885.

Technical and Vocational Education (TVE)

Vocational education is conceived to specifically prepare the student to for working life. It is also said to be closely related to, but not identical with, the concept of training (or vocational training), which tends to focus on learning specific skills that are required in particular workplaces. It is dispensed at the technical colleges, which are equivalent to the senior secondary education but designed to enable the individual to acquire practical and technical skill, basic and scientific knowledge and attitude required as craftsmen and technicians at sub-professional level.

Mass Literacy, Adult and Non formal Education

The main aim of mass literacy, adult and non formal education as defined in the National Policy on Education (NPE, 2004) is to encourage the participation of youths and adults in all forms of functional education dispensed to youths and adults outside the formal school system, such as functional literacy remedial and vocational education. It is also to provide functional literacy and continuing education for adults and youths who have never had the advantage of formal education or who did not complete their primary education. These include the nomads, migrant families such as migrant fishermen and their families, the disabled and other categories or groups, especially the disadvantaged gender. This mode of education is all the more important in Nigeria as literacy rate was estimated at 61% in 2013 (National Population Commission), meaning that about 70 million Nigerians are non-literate. Structures put in place by the policy include the National Mass Education Commission at the federal level, the State Agencies for Adult and Non Formal Education and the Local Government office of Adult Education.

School Inspection and Supervision

The challenge of providing quality education relies much on the inspection and supervision of educational services. Inspection and supervision are two complementary processes in quality assurance and relate to the monitoring of instructional practises and performance of an educational establishment. Inspection concerns evaluation by external agents, and is carried out by Federal, as well as State Inspectors. Supervision is an internal process carried out by School functionaries such as the principal, vice principals or heads of departments or other state-designated personnel.

Higher Education

Higher education encompasses all organized learning activities at the tertiary level. The goals of tertiary education, as specified in the policy are:

• To contribute to national development through relevant high-level manpower training;

• To develop and inculcate proper values for the survival of society;

• To promote scholarship, community service, national unity and international understanding; In Nigeria, higher education is available in four main types of institutions:

• Universities, which now number about 129;

• Polytechnics, originally intended for middle and high level technical/professional education;

• Colleges of Education, intended for high-level nongraduate teacher education, but some of which have since become “degree-awarding institutions” with emphasis on Bachelors Degree in Education;

• Monotechnics: higher institutions offering courses in specific professional areas: Nursing and Midwifery, Agriculture, Veterinary Studies, etc.

Directories of universities, polytechnics and colleges of education feature among the appendices of this publication.

Nigeria’s first institution for tertiary education was Yaba Higher College, established under the British colonial administration in 1932. This became the nucleus of the first University College, established in Ibadan (now in Oyo State) in 1948. The attainment of political independence in 1960 was accompanied by expansion in the education sector in general and in higher education in particular, with the University College of Ibadan becoming a full fledged University. There was later an improved geographical spread of universities: University of Nigeria, Nsukka (in the East) was set up in 1960, Ahmadu Bello university, Zaria (in the North), University of Lagos and the University of Ife (both in the Southwest) – all established in 1962; the University of Benin (South) was established later in 1970. These institutions are now collectively known as “First Generation Universities”.

Regulatory Bodies for Higher Education in Nigeria

The year of 1975 witnessed the emergence of Nigeria’s “Second Generation Universities”. Most of these had begun as satellite campuses of existing universities: Kano, Jos, Maiduguri, Calabar, Port Harcourt, and Ilorin. More universities were to follow in subsequent years. The 1990s saw the birth of private universities. This broadened the scope of ownership of universities into Federal, State, and Private and further developed the geographical coverage of the country by tertiary educational establishments. The post-1990 institutions are now collectively called “Third Generation Universities”.

Some of the universities are specialized institutions focusing on Science and Technology (Federal Universities of Technology of Minna, Owerri, Akure…), or on Agriculture (Federal Universities of Agriculture of Makurdi, Abeokuta, and Umudike). The National Open University of Nigeria is a unique institution, established in 2002 to provide access to education for those who could not be admitted through Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB). The Nigerian Defence Academy, Kaduna, has also been expanded to include a University – Nigerian Defence Academy University.

The National Policy on education also gives the opportunity for individuals, private bodies, and different levels of government to establish higher institutions. The guidelines for establishing institutions of higher education in Nigeria stipulate that an institution of Higher Education may be sponsored or owned by the government of the federation, or a state government, or by a local government, or any of the following: A company incorporated in Nigeria, or an individual or association of individuals who are citizens of Nigeria, and who satisfy the criteria set out in the schedule to this Act for establishment of Institutions.

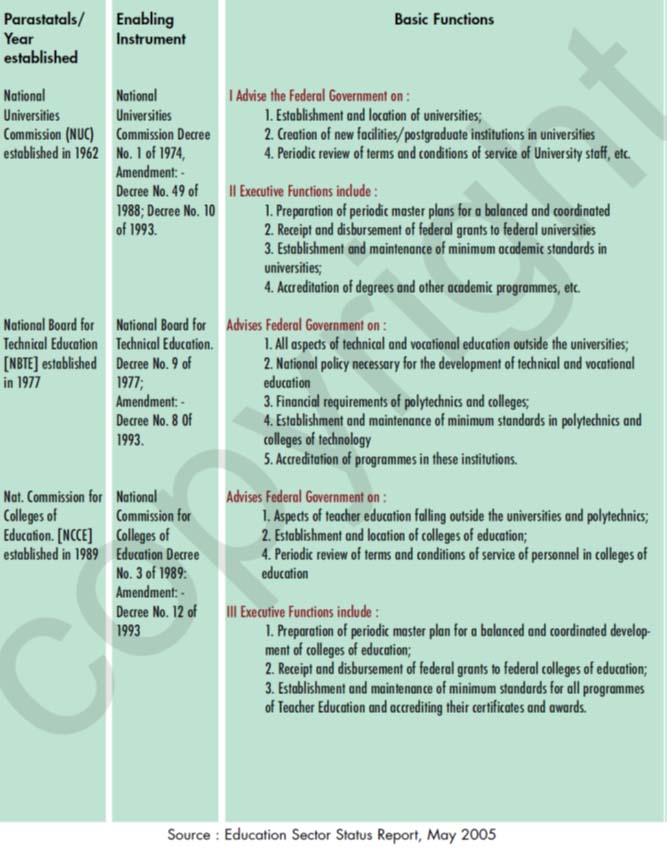

The National Universities Commission (NUC), the National Board for Technical Education (NBTE), and the National Commission for Colleges of Education (NCCE) are vital parastatals of the Federal Ministry of Education for ensuring effective administrative control of higher education in Nigeria. They help to plan, organise, manage, fund, supervise and monitor provision and development of the tertiary institutions.

Each parastatal helps to ensure minimum standard and quality among the institutions and accredits their courses. They also play the intermediary and advisory roles between the federal government and the institutional authorities.

ATTRACTIVENESS OF TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS AND COURSES

Most candidates for tertiary education prefer the University, followed by the polytechnic and the college of education, although these institutions may have different entry requirements which must be met. This is a major educational development challenge. There is also the issue of streamlining the certificates delivered by these different tertiary education systems, where they overlap (diplomas, certificates of education…). The Federal government is addressing a longdrawn contention by Polytechnics demanding that they be upgraded to degree awarding institutions, like universities, to enhance the recognition of their certificates and eliminate perceived discrimination faced by their graduands in the employment market vis-àvis their counterparts holding university degrees. However, it should be noted that for several decades, polytechnics and colleges of education were considered as gateways to quick employment as their graduands where in high demand in the job market. This notwithstanding, colleges of education continue to exercise some attraction due to the dearth of qualified teachers.

GENDER BALANCE PERSPECTIVES

There is a predominance of males in the universities, while the gender gap is narrower in the polytechnics. This reflects the relatively lower number of girls participating primary and secondary education. The situation is inversed in the colleges of education where there is a predominance of women.

The situation however hides a few unpalatable details :

•Women are predominant only in the non-scientific and non-technical disciplines in the universities;

• The preponderance of girls in the “feminine” disciplines of secretarial studies and administrative studies creates the wrong impression of a relatively narrow gender gap in the polytechnics;

• The low status of teaching as a profession is a major explanation for the relatively high enrolment of girls in colleges of education.

Gender barrier in accessing higher education is therefore a real education development challenge in Nigeria. The government in 2012 commenced the implementation of a Four- Year Strategic Development Plan for Education which focuses on “access and equity”, and “standard and quality assurance” among other highlights.

The Challenge of Funding Education

The main source of funds for education in Nigeria is the government. However, with the increasing demand for education on public finances and the fact that government alone cannot shoulder the burden of education, the financing of education delivery was opened up to other players, such as corporate organizations, communities, philanthropists, international development partners, multinational and national corporations, etc. At present, private sources account for over 20% of total national expenditure on education. Another major source of funding education is the Education Trust Fund (ETF) established in 1993 to receive education tax from companies registered in Nigeria and use it to support education through an Education Fund.

The Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) granted N24.0 billion (about 150 million USD) to six universities, three polytechnics and three colleges of education to improve their infrastructure and services and enhance quality and output (CBN, 2012).

In the framework of the Education Transformation Programme, the Federal Government awarded a contract of N5.0 billion (about 30.0 million USD) – (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2012) for the implementation of the second phase of the Almajiri Education initiative, aimed at providing free primary education to over 9.5 million Almajiris (Quranic school pupils). This has enabled the construction of 35 Almajiri Model Schools and the enrolment of over 800 pupils. Also, under a loan agreement between the Federal Government and the Islamic Development Bank, 98 million USD will be made available to further boost Almajiri and girlchild education (CBN, 2012).

Management of the Education System

Education features in the concurrent legislative list in the 1999 constitution that provides the legal framework for educational management in Nigeria. This implies that both Federal and State Governments have legislative jurisdiction and corresponding functional responsibilities with respect to education. By this arrangement, although a few functions are exclusively assigned to the Federal or State Government, most of the functions and responsibilities are in fact shared by the three tiers of government (Federal, State and Local Governments).

Statutorily, the Federal Ministry of Education (FME) is at the apex of the regulation and management of education in the country. It is advised in the discharge of its responsibilities by the National Council on Education (NCE), the highest policy-making body on educational matters which is composed of the Federal Minister of Education and the State Commissioners for Education. The NCE operates through the instrumentality of the Joint Consultative Committee on Education (JCCE), composed of professional officers of the Federal and State Ministries of Education.

Furthermore, in the National House of Assembly, legislative committees in the Upper Chamber (Senate) and Lower Chamber (House of Representatives) are constitutionally saddled with oversight functions in the education sector. Similar oversight functions are performed by the education committees of various State Houses of Assembly and Local Government Councils.

Civil Society Participation

Civil Society Participation Civil society partners play a very active role in the development of the educational sector. They include the Parents Teacher’s Associations (PTAs), National Parents-Teachers Association of Nigeria (NPTAN). Other groups involved are professional associations such as Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), the Nigeria Union of Teachers (NUT), as well as interest groups such as the National Council of Women Societies (NCWS), NGOs and community-based organisations.

These partner organisations play vital roles in amplifying government efforts in the areas of improvement of classrooms, hostels and other physical facilities in educational institutions. They also participate in the thrust to provide effective management and regulation of the Nigerian education system.